Wrap-Up

Wow, what a year! Congratulations to the 294(!!) teams that finished the hunt, and to the 811 teams that solved at least one puzzle! The first three teams to defeat Kero and finish the hunt were:

Among the fastest solvers, this was the most closely contested Galactic Puzzle Hunt in history, with many teams in contention for the top spots.

We also had a speedrun leaderboard, and were very impressed to see competing teams sail past our internal fastest total time of 29m29.054s. Congrats to those teams, who all speedran our hunt in under 20 minutes:

- , , , , , , ,

This year, Galactic Puzzle Hunt had a significantly different format than in the past, with a smaller size and about half of the puzzles being based on the GalactiCardCaptors game. Creating GalactiCardCaptors was a wild journey for the writing team, and in this wrap-up we would like to share how it came into creation, to reflect on what lessons we learned, and to muse on some puzzlehunt philosophy.

If you want to jump ahead, you can find more fun stuff at the end!

Hunt summary

At the very entrance of the GalactiCosmiCave, you find a treasure chest, surely filled with great riches. But inside the chest is Kero, a magic carp! Kero informs you that opening the chest has unleashed CHAOS throughout the cave! \(º □ º l|l)/ Fortunately, Kero also gives you the uwuand, a magical wand that converts cave dwellers into cards friends that you can use to battle! Using the power of the uwuand, by solving puzzles and playing GalactiCardCaptors, you befriend the 12 legendary creatures living in the cave.

But, all is not well; for every legendary that you befriend, Kero gains a body part and grows stronger. After befriending all 12 legendaries, Kero turns on you! With the legendaries united, you defeat Kero in a final battle. You are given one last choice: seal Kero back inside the treasure chest, or invite him to join you for some pie?

Look carefully and you’ll see what the first team chose:

If you want to see the plot in more detail, go watch all of the cutscenes!

Final faction scores

Near midway or thereabouts through the hunt, a team could choose to align itself with one of the five factions dwelling in the cave, and therewise earn a smidgen of points during battles.

- Dinos: 4850820

- Cows: 4446436

- Bees: 3409702

- Dryads: 2082386

- Boars: 1787669

Golly, we haven’t seen a closer race in millennia! I daresay we Dinos were on the brink of settling for a humble bronze, but lo! That dash of vim, that final surge! Methinks we right put those Cows in their place, did we not? (Granted, we’ve since reconciled our differences, but who doesn’t relish a good-natured tussle?)

Hats off to , whose efforts furnished a staggering >50% of our final tally. Yet, let us not forget all our other Dino supporters, for without your stalwart backing, our triumph would’ve been naught but a dream! Huzzah, huzzah, to one and all!

Writing the hunt

Goals

Our main goals when we kicked off hunt writing were:

- more cross-team interaction (PvP Arena! Also speedrunning, and faction competition)

- more beginner friendly (We almost quadrupled the number of finishing teams, so even if we account for smaller team sizes, this was a huge success)

- make every puzzle important (See Philosophy)

- decrease competition (We think adding multiple leaderboards helped alleviate the “one true winner” effect)

- less website shenanigans (We did not succeed at this, our Overworked Web Operatives need a break)

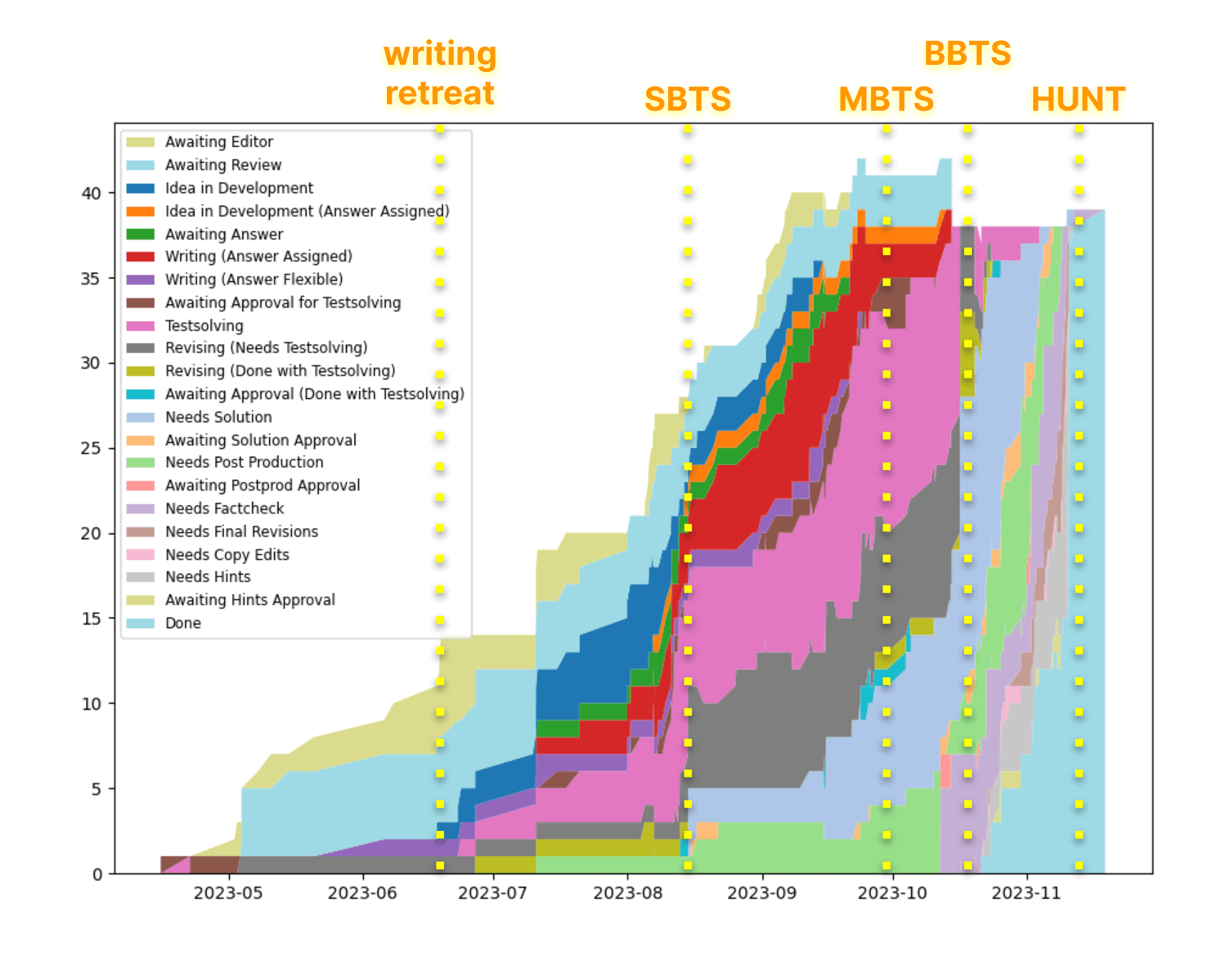

Timeline

- February: kickoff meeting

- March: theme decision.

- April: story, structure, game design

- May: base game ready to play

- June: writing retreat, hunt announcement, story again

- August: Small Big TestSolve (Small BTS), mastery meta, kero battle

- September: Medium BTS, all battles

- October: Big BTS, all battles and answerables, load testing

Theme

From our past experience writing GPH and MIT Mystery Hunt, during the theme proposal phase we have seen several “arms races” between different theme ideas, trying to be as fully developed as possible to maximize the chance of being selected. While this might make the hunt-writing later a bit easier, it risks wasting valuable effort that went into other unselected themes (even though they might be re-proposed later).

Therefore, this year we decided to have two phases of theme proposal:

- In the first phase, different themes were proposed as “elevator pitches” (two sentences max!), giving an overview of the story. This allows us to establish a full-team buy-in before we more fully explore the idea.

- In the second phase, we proposed different ways to develop the theme selected in the first phase, including specific hunt structure and mechanics.

We received fourteen theme pitches in the first phase, and the winning pitch was Galactic Card Patrol:

Deployed across the galaxy, teams solve puzzles to collect Galactic Cards, manifestations of ancient alien technology, which they use to unlock secrets and overcome challenges. These cards have unique abilities, and can be combined for unexpected and powerful synergies.

In the second phase, there were seven proposals, including two “partial” ones that were meant to be integrated into other proposals if possible (e.g. as one round or an additional mechanic). When voting, we considered how exciting the theme was, how willing people were to work on the theme, as well as strengths and potential risks of the theme. The winning proposal, GalactiCardCaptors, was centered around the premise that “each puzzle is a bespoke card battle with an enemy, and defeating it captures them into a card”. While this premise was somewhat relaxed during the writing process, much of the original vision made it into the hunt you played!

As we had hoped, some aspects of the unselected proposals from the second phase also managed to make their way into the hunt in some form:

- Playing cards as letters (Spelling Bee)

- Collecting other “real-life cards” (Mastery Tree)

- Factions and faction leaderboards

- Card battles with other teams (PvP Arena)

Answerables

As early as announcing the winning theme, we decided to include answerables, traditional puzzlehunt puzzles with answers, in our hunt as well. (This may seem obvious to experienced puzzlehunters – keep in mind our theme proposal was comfortable leaving answerables behind entirely!) More than just being familiar staples of hunts, we wanted answerables to diversify the experience of the hunt (allowing both writers and solvers who are not so into card games to contribute), as well as possibly provide some additional benefit to the card game. We intentionally asked writers for answerables to be short to not draw too much attention away from the main theme.

Ideas for answerable rewards included card upgrades (à la Slay the Spire), additional copies of existing cards, card cosmetics, and awarding “booster packs” of new cards – the last of which ended up in the final game!

When possible, we tried our best to match thematic card rewards to answerables (as well as non-legendary battles): the two best pairings are getting with Limericks and getting after beeBay Fulfillment Center.

We have more thoughts about answerables in our Reflections section.

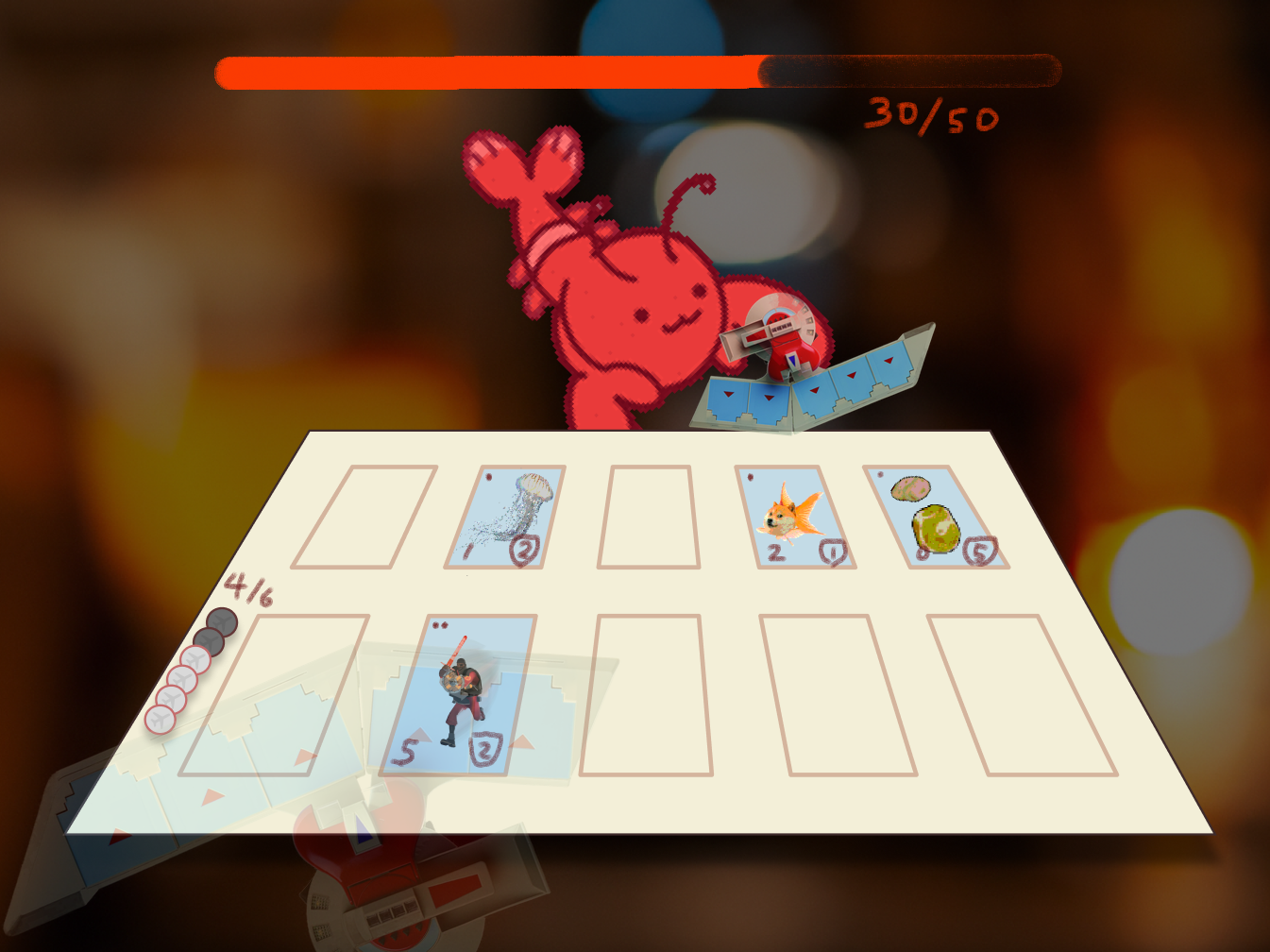

Card game design

As soon as the theme was finalized, we started drafting, playtesting, and iterating on designs for what would eventually become GalactiCardCaptors.

The first design of the game (from the theme proposal) was inspired by Inscryption/Air Land Sea/Marvel Snap, with players taking simultaneous turns, opposing cards attacking each other, and dealing damage to the player’s “life points”. This design then evolved to a larger, 6x5 grid with different terrains that cards automatically moved down – and the win condition changed to controlling three or more columns.

We experimented with many additional features, like cards having “sets”/”suits”, and additional “types”/”elements”. Inspired by Radlands, a tabletop card game, we drafted a new design centered around defending Bases, cards which produce Energy for other cards to take actions.

This latest design also added six colors to the game, with cards from each color having different playstyles. Sound familiar? This is also when “protection” – placing cards in front of other cards to defend them – was added.

When we playtested the GCC “Radlands edition” in Tabletop Simulator, we found that the emergent gameplay of the Energy mechanic (later renamed to Gems, which finally became Food) created deep strategic choices: should we attack with a creature this turn, or create food to play stronger creatures? How strong of a board presence do we need to “ramp up” to before we can attack? Should we defensively protect our Camps first, or attack aggressively? Finding these classic card game tradeoffs in this design really solidified this ruleset, and we found ourselves having a lot of fun playing matches with basic cards against each other.

Having finalized our base game, we went to work getting the game prototyped and playable so that we could start designing cards, and most importantly, designing card battle puzzles. Once we had the basics of the game implemented, we hosted a writing retreat for everyone to learn the rules of the game, play in a big tournament, and start iterating on battle puzzles.

Battles

We have lots of interesting stories about writing our battles: see our Author’s Notes in the solutions for each battle!

Early on, we divided battles internally into what we called “just battles” and “puzzle battles”, the latter of which would involve more enigmatic insights, like Coloring and Slime. This distinction ended up not really mattering both publicly and internally, especially since there isn’t a clear line between the two. Once the Kero fight was designed, we decided to communicate the “legendary battle” (👑) and “non-legendary battle” (⚔️) distinction instead, since it was more important thematically and structurally to know which battles were key to solve. All our battles are puzzles! 😙

Testsolving

We had three “big testsolves” (BTSes) starting from August to October. The first (Small BTS, or SBTS) was internal and tested about half the battles (including Mastery Tree and the Kero fight). The following Medium BTS (MBTS) and Big BTS (BBTS) tested all the battles and most/all of the answerables. Our hunt really came together thanks to our BTSes, which helped give early feedback and iteration cycles on our hunt flow, puzzle & game design, and user experience. Thanks so much to our BTS testsolvers for making our hunt as polished and cohesive as it is.

Reflections

Overall

We knew that the card game could be polarizing. There were a variety of considerations that went into choosing it anyway, but ultimately, we wanted a cohesive whole-hunt story/experience and this theme generated the most interest on the writing team. This went more or less as expected: we received feedback that some solvers who enjoyed past GPHs didn’t enjoy this one at all, but also many solvers who said this was their favorite recent hunt, or even favorite hunt of all time. Of particular interest, we got feedback from multiple solvers who didn’t expect to enjoy the hunt at the beginning, but ended up loving it by the end, which we are very happy about. That said, we appreciate all the solvers who tried the hunt and didn’t like it, and we hope that you will find future GPHs to your liking.

What is a puzzlehunt?

Is this a puzzlehunt? This question has been the topic of much discussion, both internally and externally. It turns out that this is not just semantic nitpicking, but an important aspect of how we talk about and advertise hunts.

While there isn’t a definite answer to this question, the best alternative we could think of to describe our hunt was a “puzzle game”, and we do think, at least, that our hunt is closer to a puzzlehunt than it is to a puzzle game. (We also considered something more vague like a “puzzle experience”...). The most important reason we decided to call GCC a puzzlehunt was to push the established boundaries of hunts rather than defining ourselves as outside that boundary.

Even if we excluded the 18 short answerables and the mastery tree meta, we think that many of the battles’ primary mechanics were closer to something you’d see in a hunt puzzle than in any puzzle or strategy game, in that they are novel mechanics that appear in only that puzzle and often aren’t explained; figuring out what they do is more important to the solve experience than figuring out their consequences.

Examples include deciphering the words in Dargle, determining the symbols in Jabberwock, understanding the rules in Moonick, and understanding the slime splits in Slime. Additionally, some puzzles like beeBay and Spelling Bee require minimal card game strategy and mostly feel like self-contained interactive puzzles.

On the other hand, there were also several puzzles that required a significant amount of strategy to solve (e.g., defeating Slime).

A highly subjective table might look like:

| \ Game insights

Nongame insights | low | medium | high |

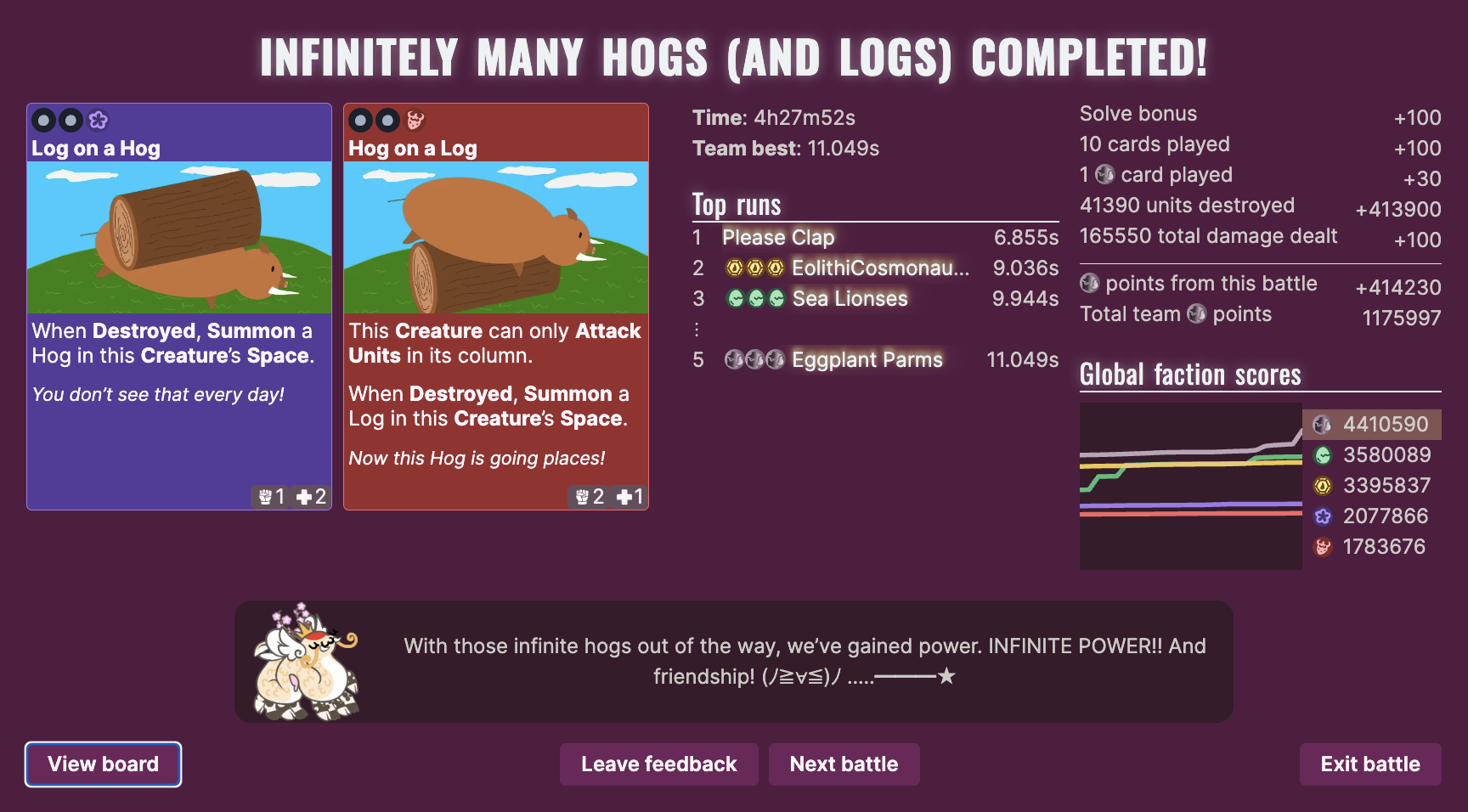

| low | Angry Boarry Farmer, Gnutmeg, Infinitely Many Hogs (and Logs) | bb b, Asteroid, The Swarm, Kero, Spirit of the Vines | |

| medium | Spelling Bee | Dargle | |

| high | Moonick, beeBay | Othello, Jabberwock, Coloring, Miss Yu, Mister Penny | Slime, Blancmange |

At an even higher level, the way we envisioned most solvers would participate in our event — by forming teams and collaboratively doing puzzles at the announced time the hunt was running — is much closer to a puzzlehunt than a puzzle game.

We should mention Jack Lance (the real Captain Pi)’s Root Three Riddle Search, whose release coincided with our theme proposal deadline. While we weren’t directly inspired, we think the RT3 puzzlehunt reflects similar thoughts we have about pushing the boundaries of traditional answerables and puzzlehunt structure.

Pre-hunt information

When we first announced the hunt, we were very conservative about what information we released, since we too had very little idea what to expect from the hunt at the time. It wasn’t until receiving feedback from BBTS when we knew that many solvers would appreciate more pre-hunt information to set appropriate expectations about the hunt.

Even then, just how much more information we wanted to release was a subject of much internal debate. On one hand, we wanted to preserve the surprise and the excitement of speculation on the theme – which many of us felt was an integral part of the hunt experience – as well as avoid creating preconceptions about the hunt and what solving it would be like. On the other hand, expectations can have a very large impact on how a solver interacts with different aspects of the hunt’s mechanics, and, ultimately, their solve experience – and, in our case, the precedence of prior GPH shenanigans might not have been enough to prepare solvers for just how unusual this hunt would be.

We ended up adding an FAQ item revealing that many puzzles would feel more like “puzzle games” than puzzles in previous GPHs, but that there would still be traditional puzzles. We tried to make it stand out by adding an alert to the top of the About page, and encouraged solvers to read that page in an email we sent out a week before the hunt. We hoped that this would strike a good balance by widening solvers’ expectations without giving too much away.

We had also considered releasing some information about hunt difficulty, but decided against doing so in the end. We knew from prior experience that hunt difficulty was very hard to predict, and were wary about making promises about it before the hunt. This was particularly the case this year, as we expected that the card game aspect would create a large amount of variance in difficulty for teams.

Our approach to managing solver expectations worked for some but not others. Many solvers were still caught off-guard by the hunt’s format, and some have expressed that it would have helped to know more about the role that battles and answerables were intended to play in the hunt. As hunts continue to experiment with new and interesting ways to break the mold of the traditional hunt format, we hope that this hunt would serve as a useful precedent to help future hunts set solvers up to get the most out of their hunt experience.

Tutorial

Designing the tutorial was challenging. We needed to communicate a large amount of information to solvers in a way that was engaging, easy to absorb, and accessible to solvers with all kinds of backgrounds, all without feeling too long or handhold-y. To this end, we subjected the tutorial to more playtests, revisions and tech work than any other puzzle in the hunt.

One of the key design choices we made was to introduce game mechanics through small puzzly challenges as much as possible. We hoped that this would not only make the tutorial more engaging for our target audience, but also help solvers absorb information better by immediately applying what they’ve learned. This philosophy informed the design of stages 3 and 4.

We also wanted to ease solvers into the more strategic, open-ended thinking required in many battles. This led to the creation of stage 5, and the intentional placement of Angry Boarry Farmer right at the start of the hunt.

The tutorial we ultimately released had its flaws. Teams found it harder than we intended, with a large percentage (~5%) of teams spending a lot of time on stage 5 early in the hunt. In response, we issued an erratum clarifying that the enemy battler was not food-limited, along with some tips for that stage.

Keepsakes

Part of teasing the hunt theme involved sending s to early donors from our 🪙 donation page 🪙 when we announced the hunt. We were hoping this would subtly clue our theme, that GCC stands for something other than GalactiCosmiCave, and that cards would be involved.

We were hoping that keepsakes could stoke public discussion of theme predictions, which we have a lot of fun reading. Unfortunately, this didn’t really happen much. Also, many US recipients had their keepsakes lost in the mail, possibly due to border issues. We’re very sorry about this! If you claimed a keepsake in August, never received it, and haven’t contacted us about it, please let us know ASAP at contact@galacticpuzzlehunt.com.

That said, we later learned that at least one team correctly guessed (in private) the Cardcaptor Sakura reference from their keepsake!

A lot of work and care went into designing the keepsakes, getting them printed, and mailing them out, but it was worth the effort to thank you for supporting our hunt! If you’d like to support our work, please see our 🪙 donation page 🪙. There is a limited number of additional keepsakes available.

The Future of GPH

Will there be a Galactic Puzzle Hunt 2024? Join our mailing list to be the first to know!

In the interim, you should check out some of these other puzzlehunts coming up:

- Huntinality III: Hunts Upon a Time (December 1)

- MIT Mystery Hunt (January 12)

Check the Puzzle Hunt Calendar for more. We’re excited to see what new ideas the community comes up with!

More reflections

This section goes into quite a bit more detail about the various aspects of the hunt-writing/designing process, written by the leads of different departments of our team.

Philosophy

Puzzlehunting is a hobby that involves many diverse interests. Despite the open-ended nature of puzzles without instructions, the structure of hunts have crystallized into a standard format: solving answerables, puzzles with answers, which are used as “feeders” in meta-answerables that act as “capstones” for progressing the hunt story and structure.

Puzzle answers are single words or short phrases, so answerables are designed around the solver trying to condense all the information into a single word or phrase.

This has led to a lot of institutional knowledge over time:

- common extraction techniques like indexing, diagonalization, eigenletters, A1Z26

- advanced solving tools like nutrimatic, onelook, qhex, util.in

- because the answer is a sensible word or phrase, it can often be obtained without solving or understanding every individual clue or sub-answerable, and may be designed with such a solve path in mind

- especially when the cluephrase starts with “ANSWERIS” or similar (relatedly, we intentionally banned the phrase “call in”, which is past Mystery Hunt-specific terminology that confused many teams in past GPHs, when our “Submit an answer” button read “Call in an answer”)

- backsolving from knowing the constraints of a meta-answerable

- counting the number of clues in an answerable, or feeder answers to a meta-answerable

Sometimes, answers are also forced into interesting standalone puzzles that are fantastic on their own and have no need for an extraction outside of the hunt – from classic puzzles like crosswords and logic puzzles to activities like interactive games and scavenger hunts. This definition of a “hunt puzzle” is extremely narrow, despite the fact that we like to explain to newcomers that they can “be about anything”. It’s no wonder we have a hard time explaining puzzlehunts!

This standard format also offloads much of the effort of writing thematic and cohesive puzzles to metas themselves. While metas can place interesting constraints on their feeders, it’s often the case that a feeder answerable is free to use nearly any mechanic, as long as it solves to the assigned answer. By design, authors are free to write any answerable they want – at the expense of a less narratively relevant and thematic puzzle.

Because of these thoughts, one of the main goals of our hunt was for every puzzle to be important, thematic, worth engaging in, and part of the structure of the hunt. Solving each puzzle should be its own reward, and we wanted to explore other ways of tying together puzzles into a hunt package. As you can read from the winning theme document, the initial proposal was so far along the “anti-meta revolution” that it only described card battles, which were intended to be the full experience of hunt; the interaction between capturing new cards to use in other battles (and losing cards in special battles, like the “black hole”) was a cohesive and rich enough design space that metas (and answerables) didn’t feel necessary to tie together the puzzles.

In the end, the final Kero fight became more of a traditional metapuzzle (tying all the legendary cards together), and the Mastery Tree round was introduced to provide more variety to the hunt, so we leaned back a bit from the initial purist anti-meta vision. To those of you debating whether our hunt was a puzzlehunt at all – consider how far we were willing to go! In fact, many of our theme ideas this year involved novel ideas that would break established puzzlehunt patterns.

We hope the context change that GalactiCardCaptors provided gave beginner teams and the larger puzzle-curious community more equal footing with experienced teams. There is a point in our hunt when every experienced team says, “we finally unlocked real puzzles” – a value judgment that only those entrenched in the existing framework could have. We hope to see the puzzlehunt community grow and continue to innovate beyond answerable puzzles, and stay inclusive and open-minded of attempts to do so.

Puzzle design

The structure of the hunt this year brought with it many challenges for puzzle writing. Over the years, we’ve learned quite a lot about designing round structures, metapuzzles, and traditional hunt puzzles, but much of that knowledge was not very useful to us this year when we started working on card battle puzzles.

For a few months after deciding on the theme, we weren’t sure exactly what card battle puzzles should look like, and it was especially difficult to design them for a variety of reasons:

- The exact mechanics of the card game that we wanted to build them on top of took a while to decide on, and there was a feeling that the direction of the first few puzzles to be written would help decide the design of the card game.

- Early on, we had agreed that puzzles could vary the mechanics significantly if the authors wanted, to allow for puzzles like Spelling Bee and Othello. However, this made the potential design space overwhelming.

- There was a significant “ramp-up” required to understand the card game before writing a puzzle, so authors not heavily involved in the hunt writing process found it difficult to participate.

- Authors less involved in the technical implementation of the hunt weren’t sure of what exactly would be reasonable to implement, and found it harder to write because they would also need to ask someone else to help implement their ideas.

For these reasons, one of the top priorities at the beginning of the writing process was to get a few puzzles written as soon as possible, so that other writers could see what a card battle puzzle could look like, and to help solidify the process of writing card battle puzzles.

During this period, there were significant concerns that we would not be able to run the hunt as planned, because it was really quite tricky to get the first puzzles written. It took until early July to get the first card battle puzzles into a testable state, and (along with the significant amount of technical work required) was one of the reasons for this year’s hunt happening later than previous hunts.

Some of the first puzzles to be fleshed out and written were bb b, Dargle, and Blancmange (although they all had very different names at the time). Some trends that we noticed:

- Early puzzles didn’t use the “sub-battle” concept (Dargle was converted to it later), because we hadn’t created it yet, which made it harder to make them feel substantive while also being approachable. For instance, the initial version of Dargle was quite difficult in testing, because it required defeating all of the waves at once sequentially, similar to Kero.

- Early puzzle battles tended to be based around “gimmicks” because the full deck of cards hadn’t been fleshed out yet, so it was ideal to design around only needing a small number of cards to complete them. Many of the battles based more around the “fundamentals” of the card game were added in later.

While we are happy with the set of card battle puzzles we came up with, a lot of us on the writing team learned a lot about designing these types of puzzles after the internal “big testsolve” events, and might be able to come up with a lot of new, interesting ideas if we were to design a new set of card battles now 😉.

The Mastery Tree and answerables

The answerable puzzles (i.e., the puzzles with traditional puzzlehunt answers) in this hunt were intended to complement the card battle puzzles, both for the writing team and for solvers. Some reasons for the inclusion of the round, from my perspective:

- While we intended for the card battle puzzles to appeal to traditional puzzlehunt enthusiasts, we wanted there to be some familiar puzzles for hardcore fans of those types of puzzles.

- Newer authors (and experienced authors who just weren’t as involved this year) had a hard time contributing to the card battle puzzles, so the Mastery Tree round was a good way for them to contribute to the hunt.

- The card battle system was not ideal for expressing certain types of puzzles (although we did find it more expressive than one might expect beforehand), so it would be nice to have a round to include types that don’t mesh well with the card battle setup.

We targeted a lower level of difficulty for these puzzles, partially to accommodate newer and less involved authors, and also because we didn’t want to make the answerable puzzles blocking items for the card battles. For this reason also, solving answerables does contribute towards unlocking more puzzles, but not as much as solving card battles.

The first answerables in the Mastery Tree round only unlock after three card battles are solved. This was done primarily to encourage all solvers to give the card battle puzzles a try, as we felt that unlocking them simultaneously with the card battles would result in solvers who started with the card battles becoming “specialists”, whereas solvers who started on answerables would feel like they were too far behind on card battle knowledge to engage with it. This was something we had observed in the past with Puflantu in 2019’s hunt. We also did this to set expectations that card battles were not just a puzzle “gimmick” but the backbone of our hunt.

For some teams, having dedicated sub-teams working on the card battles and answerables might be ideal, as some solvers feel strongly about what types of puzzles they prefer to work on. However, we did get a lot of feedback from solvers who initially felt like the card game wouldn’t be their type of thing, but ended up really enjoying it.

Hunt structure

Since our card battles did not have traditional answers, there was some discussion early on about what sort of capstone puzzle we should have for the hunt. There were some pretty adventurous ideas, like having a simultaneous battle at a fixed time, with all hunt participants chipping away at a “raid boss” encounter. The “final battle” and legendary cards felt like a good way to bring in the fun of progressing towards a final puzzle in a way that made more sense for the card battle system.

One interesting aspect of it was that it required solvers to complete a much greater fraction of the puzzles than in a typical hunt, in which metapuzzles can often be unlocked and solved with far fewer than all of the “feeder” puzzles. We considered adding some kind of leniency, like giving solvers the last legendary card if they were only missing one, but decided against it as it did not fit well with our hunt’s theme and mechanics. Moreover, we wanted to have the flexibility for legendary cards to include spoilers for their source puzzle, or rely on having solved the source puzzle to be understood correctly. Instead, we opted to rely on the hint system to get solvers past puzzles they were struggling with. By moving the initial hint release to 12 hours into the hunt instead of the usual 24, and targeting the puzzles easier than our usual fare, we hoped that the requirement to solve all legendary battles would not become a frustrating wall for solvers.

Testsolving

We found that this hunt was more difficult than previous hunts to testsolve adequately. There were numerous enthusiastic solvers on our team who tested essentially all of the puzzles, but we felt that they would likely find the puzzles to be fairly straightforward even if solvers in actual hunt conditions would find them quite difficult, due to our testers being much more familiar with the battle system. On the other hand, it seemed like testers trying out their first card battle puzzle might find it a little more difficult than we’d expect solvers in the actual hunt to (especially for puzzles towards the end of the unlock order).

For this reason, we placed a lot of emphasis on three “big testsolve” events for tuning the puzzles and hunt structure (named SBTS, MBTS, and BBTS: “small big testsolve”, “medium big testsolve”, and “big big testsolve” respectively). We ran SBTS with about half the hunt written (including both the Mastery Tree and the Kero battle), primarily with team members who hadn’t been involved with the card battles up until that point, and then ran MBTS and BBTS with completely unspoiled solvers, with hunt writing mostly complete. Even more than for a usual hunt, these events proved particularly important in tuning puzzles, and seeing how teams might interact with the unlock structure and hunt flow.

A Story about Story

Way back in the days of yore (a time that probably only the dinos remember), a game prototype was made with colored gems as resources. The story began in a cave, where you found a crystal. You would explore the world, find help along the way, and eventually go to space to fight for the fate of the worlds! (Evil Entities trying to farm planets for the power of gems)

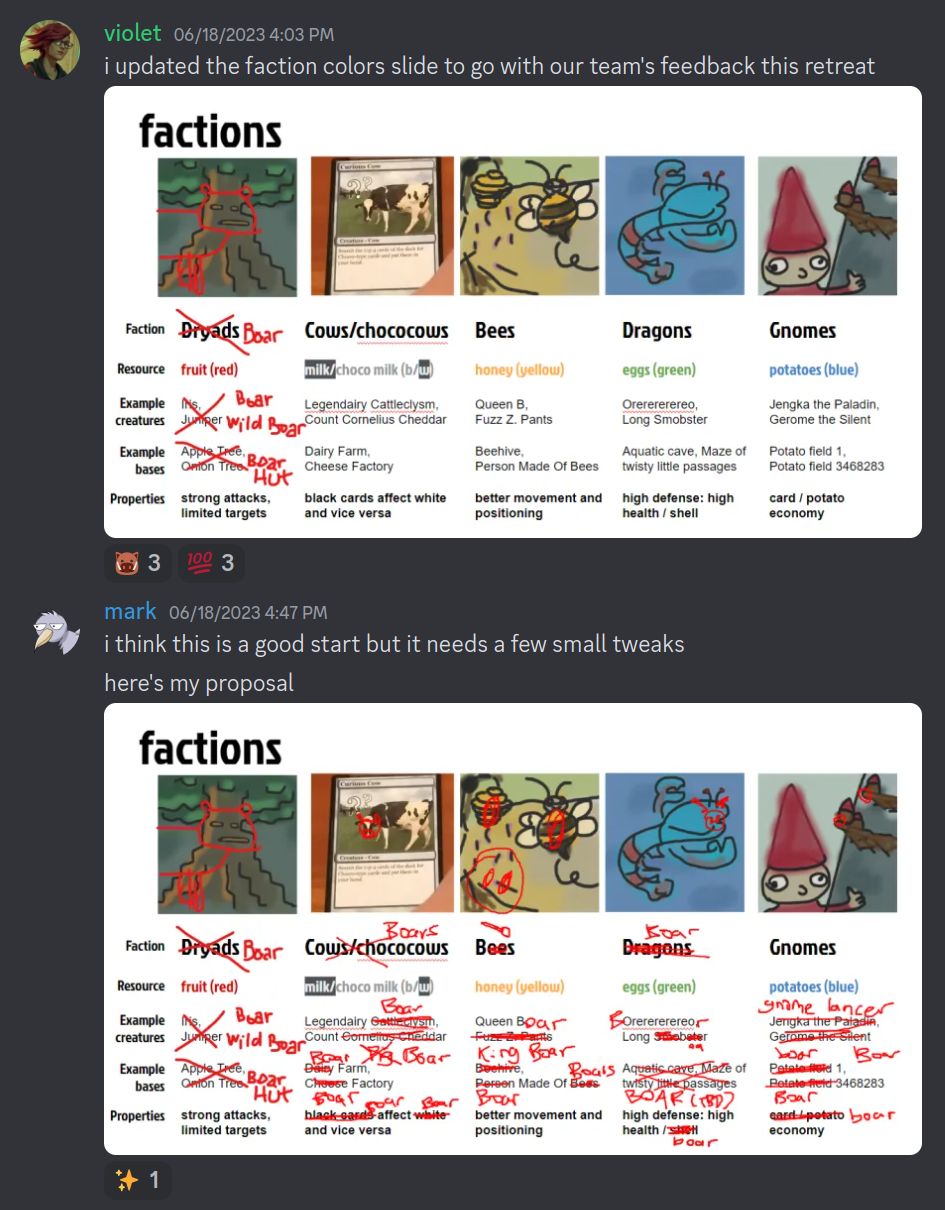

Then, came the factions. We hoped that each kind of faction might lend itself to a kind of puzzle. (e.g. the bees like spelling, the lobsters liked memes, etc.)

- Red = gnomes

- Blue = crustaceans

- Green = trees

- black/white = night/day snakes

- Yellow = bees

Come June, new blood was injected into the story. To the forefront came two ideas: cake, and a cute companion named Cerberus (inspired by Cardcaptor Sakura). Cerberus, we thought, could also be a play on the guard of the underworld, and perhaps Sakura was the Queen of the Underworld.

We wanted to stitch together enough of a story to spark ideas for puzzles and cards during writing retreat, so we made cake:

- Red = dryads, which make fruit

- Blue = gnomes, which make potato (to make into flour)

- Gnome mana is an island!

- Green = dragons, which make eggs

- Black/White = cows (same as now), but they made chocolate and milk

- Yellow = bees (same as now)

One concept we played around with was for dragons to get more powerful as they got longer, which brought us the cards o and re (who then moved on to become cows later on in their lives).

But more importantly, you ask, where are the boars?!?!

Perceptive of you to ask! During that writing retreat, we playtested what cards we had (made by Charles) in a PvP tournament. The Boar was OP, defeated many an opponent, and wooed many a heart. The retreat ended with some Gartic Phone activities in which some boars on the floors became hogs on logs, and it just became very clear that we needed more boars. MOAR! So, they replaced the dryads, and made boarries. And they got their own Discord channel. Twice.

We were also left with a couple of tough questions. Do the factions live in harmony or are they at odds with one another? In the narrative, are you playing card battles, or are the card battles actual battles? (In a funny turn of communication, proponents of both options called this “playing it straight.”)

So naturally, having finished with writing retreat, we set aside the questions, and for two months, there was little more movement on the story (this is an important ingredient of puzzlehunts — letting people and creation rest) until there was another push because of the upcoming SBTS (small big testsolve) (another important ingredient of puzzlehunts — deadline driven development). At this point, the Mastery Tree and Final Battle had been spun into existence.

The story team looked at Captain Pi and thought, we need pie.

And thus, cake became pie. For pie, one must have butter, and thus the cows changed their industry to make black butter and whipped cream (conveniently, B and W, not that the other factions have the letter of their color and resource match).

During this riffing session, we also thought, wouldn’t it be cool if Kero took on the traits of the factions, much like the Chinese Dragon is made of different animals? “Oh!” said another, “He’s Kero Dos!” And thus, it came to be that the original Kero had to be a magical carp. (Yes, it’s a play on Gyarados – who we learned later is based on a related myth!)

This led to some other conundrums.

What does the gnome provide the dragon? We must have antlers. And thus the dryads made a resurgence and replaced the gnomes, who took their silent G’s and found their way to the Gnutmeg Tree.

Why is it that Kero becomes a dragon, one of the factions? And thus, the dragon faction became the dinos. (Which, ironically, makes them actually the youngest of the factions.)

So were the factions set, and the Final Battle rethemed to relieve Kero Dos of his ill-gotten powers.

During this super-serious riffing session, it was joked that uwu could be Underwater Usurper, and because we are a very serious team, this became reality. Adding Rock Lobster was only natural at this point.

With all the story pieces set, we wrote up some example dialogue with the intention of not branching, but in the end, we couldn’t decide if the better ending was to forgive Kero and invite him to eat pie with us or lock him up in a box and start the cycle all over again. So then … the web team … just made that happen. Despite them already being underwater (hah).

The puzzles were written, and to each battle, a faction was assigned. But the factions needed homes! It was only natural that the map be split into five sections, one for each faction.

But alas, this was not to be. There were more important factors to consider when arranging battles, such as difficulty, variety, and card rewards. And so the battles were arranged without due concern for factions. The draft order looked like a mess at first, but then, a closer look revealed a most intriguing pattern. The first five battles were one of each faction, and beyond them, the battles were mostly neatly split across faction lines! You just had to ignore the cows, which were everywhere.

And that was when the truth dawned on us. Cows never belonged in one place! They were nomadic. Or, perhaps, they were just everywhere – a sprawling industry that touched every corner of the cave, a massive tax collection apparatus! And then, later, when we realized that we had no non-legendary cow battles, our eyes were opened a second time. The cows were powerful, arrogant creatures that roamed wherever they pleased.

Art

We made a LOT of art. Like, almost everyone on the team did some art or another. See our art credits!

A couple decisions we made earlier on were:

- Avoid AI art.

- Accept (and encourage!) widely varying art styles/“quality” for the cards; real TCGs do this, why not us?

Concept and “beta” art

Original prototype for Kero’s transformation: https://scratch.mit.edu/projects/900412088/

Original prototype for Kero Dos: https://scratch.mit.edu/projects/907519553/

Web

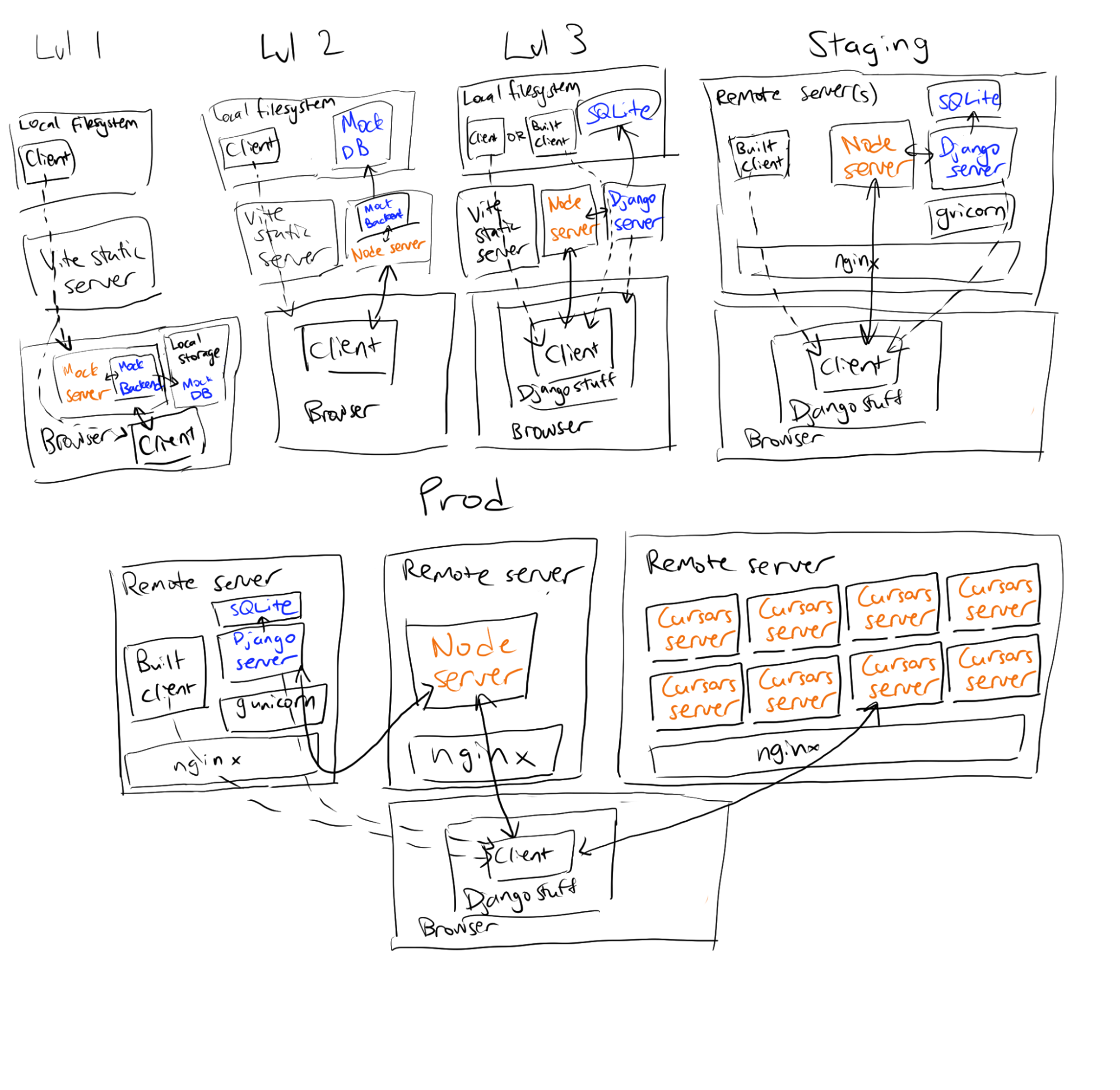

Setup

- A modified version of gph-site (Django/gunicorn/nginx/SQLite) for serving static files (directly through nginx), managing accounts, and generating non-dynamic pages (like the errata page).

- Node server (Typescript) on a separate machine to handle interactivity, which includes not just battles but also everything from leaderboards to answer submission.

- The interactivity server did not persist any data directly. Instead, it called into a custom gph-site endpoint to persist data (on-demand or periodically, depending on the kind of data).

- 8 instances of the cursors server (technically the same setup as the interactivity server, but with some env vars set to limit functionality) on a separate machine, solely to handle cursors sharing. Teams were load balanced across the instances based on team ID.

- Client based on React + Zustand, with React Router for routing, framer-motion for animations and floating-ui for layout, packaged with Vite.

The interactivity server relied on typia for validation. We used JWTs to authenticate clients to the Node servers based on accounts from gph-site. We did not rely on any frameworks for the game engine itself.

The advantage of this setup was performance. After our experiences with Django Channels in previous years, we were particularly wary of using Django Channels in any large capacity. (In fact, we still don’t have a definitive answer to what went wrong last year, though we have a few more ideas from our experience with load testing this year.)

The disadvantage is that restarting the interactivity server would have been very disruptive. This isn’t really a problem with this setup per se, since getting blocked out of an interactive puzzle for a few minutes would have been an unpleasant experience regardless of how it was set up. Given that most of the hunt was going to depend on interactivity, we chose to focus on making a server restart as unlikely as possible, instead of building in a graceful shutdown mechanism. (We did end up making a graceful shutdown protocol as a contingency, but it required users to perform a manual refresh.) Apart from doing lots of load testing and manual runthroughs, we were prepared to, and did, make heavy use of the Node debugger’s REPL to monkeypatch code on the fly in response to serious bugs or errata. We did not need to restart the server at all throughout the entire hunt’s runtime.

One thing we enjoyed a lot about the new infrastructure (but really, the highly interactive nature of the hunt itself) was the ability to spectate teams’ battles directly. We also enjoyed upgrades to the big board, the page that displays a summary of each team’s progress through the hunt. The new big board updated in real time without adding significantly to server load. It also displayed which battles each team was actively engaged in.

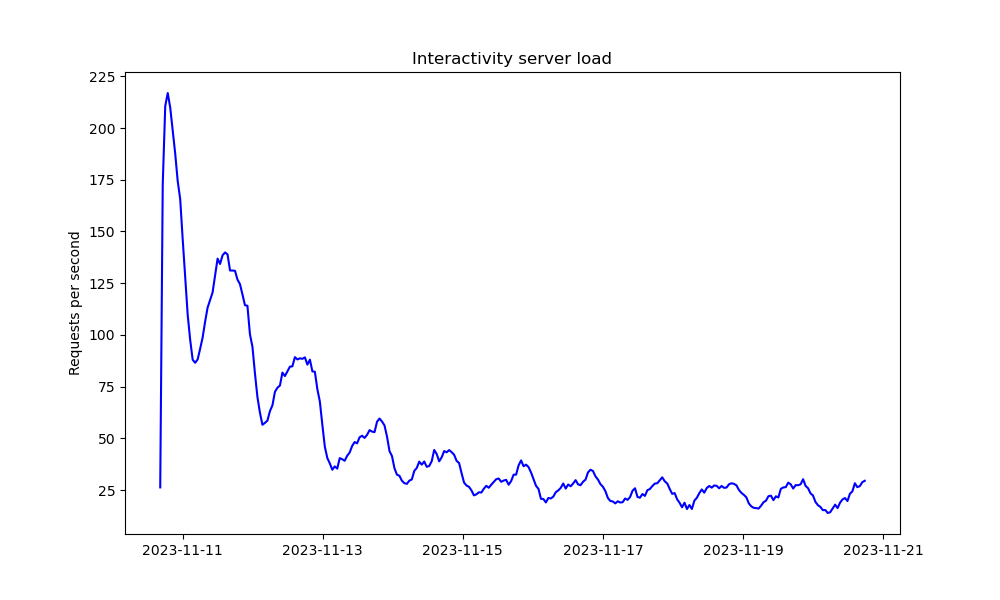

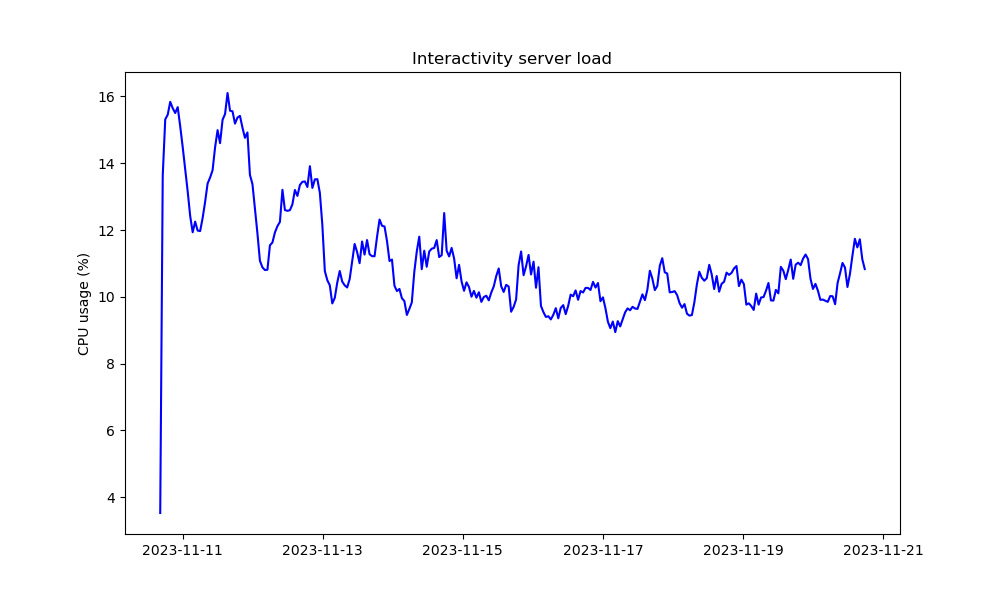

Load engineering

We made load engineering a priority for this hunt, and were glad to see that it succeeded. For context, our past hunts have been plagued with load problems, particularly last year when the site crashed as often as multiple times an hour. This caused a lot of solver frustration. We wanted to avoid this in this hunt to the best of our ability, particularly given how much of the hunt depended on interactivity.

Since we barely had any load engineering experience as a team, we made sure to set time aside for it this year. We started load testing in earnest just after MBTS, 1.5 months before the hunt date. This was actually a few weeks later than planned, but, fortunately, it worked out for us in the end.

Here are some highlights:

- Having a budget set aside for server costs helped. We ran a load testing (spot) instance continuously through the last month of hunt development just to reduce the activation energy of running load tests. We also had little qualms about overprovisioning the prod hunt servers.

- We started with k6, as recommended by other hunt organizers. However, we found it difficult to make k6 work for us. k6 had limitations on dependencies that made it hard to write tests on top of our existing hunt infrastructure, and its synchronous VU system made it difficult to simulate asynchronous websockets interactions. We eventually moved to generating load manually from one or two Google Cloud instances when it became clear that network bandwidth wasn’t a bottleneck for us.

- Our initial testing found that nginx could not support a large number of simultaneous websockets connections at once. We resolved this by setting some parameters in nginx.conf (specifically, worker_connections and worker_rlimit_nofile). It seems that we had set them in a previous GPH but had not integrated the changes into our deploy script.

- We then found that Django was rejecting sync packets from the interactivity server because they were too large. At that time, we were uploading the entire server’s dirty state in a single request every sync cycle. It took us quite a bit of work to break the sync into chunks and ensure that the chunks were all appropriately sized. This was around the time of BBTS.

- Next, we found that the server struggled to support the load from our shared cursors load test. While we already expected cursors load to be heavy for the server in theory, seeing the server slow to a crawl in testing gave us the motivation we needed to move cursors out to a separate server. Further testing confirmed that splitting the cursors load across multiple server instances improved performance, and that 8 instances was enough to synchronize cursors smoothly at our highest load setting. (Node is single-threaded, so distributing load across multiple processes removes the 1-CPU bottleneck.)

- As load testing progressed, the staging server started failing on initialization because Django was taking too much time to query initial user data. We deduced that this was because of very inefficient Django database queries, as is always the problem with Django. This was two weeks before hunt.

- Around the same time, we developed a server health monitoring page. The page reported, in real time, the sync progress of almost all objects and queues on the server, along with various other metrics. After setting this up and re-running load tests, we found and fixed a deadlock condition related to answer submission.

-

We also found that our load tests were performing significantly worse than before. Chillingly, the load tests were failing in a similar way to what happened in GPH2022. The server would appear to be doing fine for a while, and then suddenly fail to accept new connections even after the load is removed. Frantic debugging led us to deduce that the load tests were queuing up a very large request buffer for each connection. Node was spending a lot of time processing these requests even after their source connections were closed. It’s possible that our websockets server during GPH2022 suffered a similar fate.

It took us a while but we eventually figured out how to profile the server and acquire flame graphs. We found that the server was spending almost all its time in validation, a feature which we had added just a few weeks before. It turned out that Zod, the validation library we were using, was well known to be extremely slow. Right away, we switched to manual validation for cursors requests, since their high frequency made them particularly sensitive to validation performance. We later switched to typia for all other requests once we figured out how to get it set up.

-

Further load testing showed that downloading leaderboards and serializing messages for broadcast were particularly heavy operations. Fortunately, we somewhat anticipated this and were able to quickly implement simple optimizations.

- By then, one week before hunt, we had developed a load test that aimed to simulate a realistic load profile by making a large range of different request types at a rate we might expect of actual solvers. This included making game, deckbuilding and mastery tree actions, as well as periodically establishing new connections and downloading the leaderboard. We found that the server could handle up to 600 teams of 5 members each reasonably well. Since we expected most teams to have fewer than 5 members and that teams would likely not all start the hunt at the same time or be as fully engaged in the hunt, this gave us a large enough margin to go into the hunt with reserved confidence.

UI

For past GPHs, nearly everything frontend-related was built with Django templates, with no other frontend framework, because the UI was mostly simple. (It also helped that we had a great base, gph-site, to build on.) This hunt, in contrast, needed a lot of UI work, which is why we chose to add a React client early on. A lot of the inspiration for the battle and deckbuilding interface comes from existing digital card games, including MTG Arena, Hearthstone, Inscryption, Marvel Snap, and Slay the Spire. Interface In Game was a great reference for how other games structured the UI.

Development timeline

-

April. We received the first draft of the card game design on April 1st, and developed a client-only prototype for it over the next two weeks. The initial game design had a similar split field as we do now, but was different in almost every other way. Both players would construct their turns at the same time, and then both turns would resolve at once. Cards moved towards the center of the board by one space every turn, similar to Inscryption.

At this time, authors were struggling to come up with battle ideas, and it was still unclear how integrated we expected most puzzles to be with the card game. On the tech side, we used this time to split the prototype implementation into a separate client and interactivity server.

At this point, the interactivity server was not yet integrated with gph-site. Instead, it persisted data to disk by writing data directly to a JSON file. Additionally, we made it possible to run the server core directly on the client in a separate development mode, with a mock database interface that persisted data to local storage. We maintained both of these development setups all throughout the development process as they require less developer overhead. In fact, we rely on the client-only setup as our primary development setup even now.

We also implemented an initial deckbuilding interface. At this stage, the deckbuilding interface was entirely separate from the game, and required the user to manually add a URL parameter string generated from the deckbuilding interface in order to use a custom-built deck.

-

May. The month started with a new game design, along with a set of about 30 sample cards and corresponding card effects, that hoped to give a better foundation for battle ideas. The mechanics laid out in this design is essentially what we have now, barring some minor details. For example, when the design was first proposed, a creature and a structure could occupy the same space. We later dropped this mechanic when we found that it added a lot of technical complexity without making the game much more interesting. The design also called for solvers to be able to select bases as part of deck selection. This got dropped later on when puzzle battles started getting implemented assuming the default bases, but no new bases had been added to the game yet.

We spent the first few weeks migrating the prototype engine to the new game design, as well as creating a hooks model that allowed different “game specifications” to be loaded to modify engine mechanics for puzzle battles. As we still had no puzzle battles written yet, we started by creating hooks that would allow us to run the old simultaneous-turns game design on the new engine, with the aim of exploring potential modifications that an author might request for a puzzle battle.

Around the time we completed the new prototype, we added linting and prettifying to our development flow. This signified our transition out of the prototyping phase. We also added a hooks interface for implementing card effects, and implemented all the sample card effects that we were provided with. Finally, we implemented a sample PvE battle. In this battle, the opponent randomly placed “robots” that attacked every turn.

-

June. We started work on integration between the interactivity server and gph-site around this time, but it wouldn’t be until August when we completed the initial prototype. We also had a retreat planned in the later half of the month, which we hoped to use as an opportunity to get more team members familiar with the card game and inspired to design battles.

In preparation for the retreat, we implemented a tutorial, and set up the staging server deploy to support battles between team members. This tutorial was a lot more rudimentary than the one we have now, but was enough for internal use. We also added tooltips, an enemy battler avatar that could speak with a speech bubble, and a “workshop” interface for experimenting with card effects. To demonstrate what a puzzle battle could look like, we also pushed through with the implementation of our first puzzle battle, though we didn’t have it ready until the second day of retreat. This puzzle would eventually become Blancmange.

The retreat succeeded in inspiring some battle ideas. To support the renewed interest in puzzle writing, we set up a cleaner, safer hooks API, complete with automatically generated documentation with typedoc. The next two weeks would see us implement what would become Dargle and Slime. The idea for what would become Spelling Bee also came about during the retreat, but it took a while to gain traction as the authors did not feel comfortable implementing the battle themselves. We also made the battle and deckbuilding interfaces look a lot nicer during this time.

-

July. This was when we implemented the deck selection screen, at first just to select between pre-built decks. We integrated it with the deckbuilding interface later that month. At this point, players could create and delete as many decks as they wanted.

In our original design, decks were primarily managed by Django, meaning that the interactivity server had to download a player’s chosen deck from Django whenever they started a battle. Later in the month, we moved to a simpler model where deck state was entirely managed by the interactivity server, with dirty decks periodically collated and uploaded to Django.

Work also started on what would become Miss Yu, Mister Penny, Moonick, Jabberwock, and, later, Coloring and the Kero battle. Most of the tech work during this period was focused on supporting hooks for these new battles. We also implemented an initial version of checkpointing with only one save slot, and worked on infrastructure to allow teams to start, stop, and switch between game sessions.

-

August. The first draft of the mastery tree meta was completed just before the month started. We spent the first week of the month setting up the mastery tree page. Our mastery tree implementation then was a lot less user-friendly than it is now. You could not move answers around, could only place a new answer if doing so maintained a valid mastery tree, and could only remove the most recently placed answer each time.

Originally, masteries were envisioned as affecting gameplay, such as buffing the health of bases. We soon realized that this would be a nightmare to design battles around, and eventually decided to limit mastery effects to lower-impact features. We turned our attention towards QoL features like keyboard shortcuts or animation speed sliders, but came to the consensus that it would be too annoying to have them get disabled in battle while someone else was experimenting with the mastery tree. Work on mastery effects subsequently stalled until after SBTS.

Around this time, we started work on what would become Gnutmeg Tree, an old puzzle battle idea originally proposed for the old game design. We also started work on what would become bb b and Othello. This gave us the requisite 12 “feeder” battles that we needed in order to assign one battle to each legendary card.

We originally aimed to freeze the hunt’s list of battles by SBTS, However, by this time, there was considerable interest in implementing more battles, so we allowed implementation for new battles to slip by up to a few weeks beyond that. Some work on answerables had started, but we prioritized battles implementation for SBTS.

To support SBTS, we implemented support for solving and unlocking in the interactivity server, and created a rudimentary admin page and answer submission mechanism. We also started work on in-battle animations around this time. SBTS came and went successfully, giving us the confidence that we could deliver the hunt by November. In the following week, we announced the hunt. We also did a final renaming pass over the collectible cards. Modifications to the collectible cards after this would be limited.

We also had a final brainstorming session for mastery effects. It was then when we demoted the draw card ability from a base game feature to a mastery. The masteries assignment we ended up with was mostly the same as what we have now, with a few exceptions. Spark of Inspiration was assigned to base or avatar customization, while Erase Pain was assigned to “one-click mulligan” – a button that allowed you to redraw your hand if you didn’t like it. At this point, we did not have the ability to restart a battle directly from the battle screen. Rather, you had to forfeit, return to the deck selection screen, then start the battle again.

At this point, the UI was starting to get complicated. We ran into trouble figuring out how to handle edge cases with deck deletion, such as when a solver deletes a deck that another solver was deckbuilding. After a lengthy design discussion, we hit on the idea of having a fixed number of decks shared across all battles.

It was also around this time when we integrated the client into gph-site, added URL routing, implemented stage selection, and started paying attention to client performance.

-

September. We kicked off art work before the month started. Over the next few weeks, we set up minimal implementations for all mastery effects, including the PvP arena. It was at this time when Spark of Inspiration was descoped to the factions mechanic, primarily to reduce art requirements. Around this time, we made it possible to restart a battle directly from the battle screen, which took more server work than you’d expect. This made the original “one-click mulligan” idea for Erase Pain redundant. Lacking any other ideas to replace it with, we left it as a “do nothing” mastery, which we thought was funnier anyway.

We also wrote and implemented a new tutorial, which would go on to become the tutorial that we have now. To support this tutorial, we implemented a number of ambitious UI features, such as applying a mask with a cutout over the battle screen, automatically selecting and deselecting units, and attaching dialog boxes to various UI elements. We also implemented recursive tooltips, and a system for cutscenes that could also be used for the tutorial’s and other battles’ dialog sequences.

Going into MBTS, we implemented the last few battles and answerables, assigned battles to legendaries, implemented Kero’s transformation and pre- and post-battle dialogue, integrated card, battler and map art, and determined a draft puzzle order. We also added support for placing and moving masteries freely in the mastery tree interface.

Around this time, we realized that we hadn’t autoplayed rock lobster anywhere yet, and hit upon the idea to play it during the Kero battle. It wouldn’t be for another month, though, before we got the idea to replace it with the instrumental version. It was surprising just how well the music fit the battle.

We had planned to lock down the scope for major, non-QoL-related features by MBTS. Features that got cut at this stage include separate PvP scores and rankings, PvP interactivity and anti-abuse features, achievements and quests, and deeper factions integration.

-

October. MBTS went by successfully, with lots of feedback for UI improvements. Our next target was BBTS, which was our cutoff for large QoL-related features. In the short span of time leading up to BBTS, we implemented the Instancer, cursors, hotkeys, the minimap, and Kero’s notes. We also started load testing, and added buttons to jump directly between the battle and deckbuilding pages as well as between decks in the deckbuilding page.

The MBTS team had indicated a strong desire for a list of puzzles page, which we really wanted to avoid. Instead, we tried to understand what purpose they imagined a list of puzzles page would fulfill. For example, one of the main purposes of a list of puzzles page is to make it easy to see what puzzles have not been solved yet. We came up with the minimap as an alternate design that would fulfill this purpose. We only added the hotkey to move between unsolved puzzles later, when the BBTS team expressed that they missed the ability to quickly open all unsolved puzzles.

We created the Instancer in response to requests for individual battle instances, which we repeatedly got in testsolving even before MBTS. We were originally very reluctant to support having multiple instances of each battle per team, as doing so would have added considerable complexity both on the server and in the UI. It wasn’t until after MBTS when we came up with the idea of having a fixed number of separate, team-wide Instancer rooms that could be used for any battle. Such a design, while still risky, was sufficiently limited in scope to try to get into hunt.

BBTS went by successfully, with barely any issues with the website. The BBTS team’s biggest feedback was to set clearer expectations about the hunt, which prompted us to make adjustments to the hunt info page. We left it until the week before hunt to announce these changes since we also needed to determine if we wanted to commit effort to hiding spoilers in code. At the end of the month, we decided that we did not, and adjusted the hunt info page to reflect this.

The post-BBTS period also saw us finish up websockets validation, set up the server health monitoring page, triage load issues, and implement the global speedrun and factions leaderboards. We also polished up the PvP arena in preparation for the final PvP playtest, which we had scheduled for the end of the month.

-

November. We moved to typia for validation, and continued fixing load issues up to a few days before hunt. We also added the autosave and extra save slot, and made the big board update in real time.

We briefly considered using the autosave feature to implement single undo, by autosaving before every action. The ability to undo was a frequently requested feature that we had long concluded was too complex to implement directly. In the end, we chose to autosave after every turn instead, as it seemed more useful and less risky.

We conducted our final runthrough the weekend before hunt. The final runthrough served as our milestone for our final code freeze, with exceptions for features that were carefully reviewed and tested. Features that were only fully implemented after the final runthrough include the Kero animation, the infinite hogs art, sound effects, and Slime’s duplication on the victory page.

Gallery

Fun stuff

Team shoutouts

- Top speedrunners in our bonus categories (at the time of writing):

- 100% fastest time: (23:56.256)

- Fastest cutscene clicking: (The Treasure Chest, Entering the Water, The End), (Your First ANSWER), (Your First Legendary)

- Fewest turns: (canonical%, 274 turns), (100%, 524 turns)

- Fewest actions: (canonical%, 1298 actions), (100%, 2371 actions)

- Most PvP wins:

- (99 wins!)

- Most PvP wins − losses:

- (99 wins, 52 losses!)

- for finishing the final battle 6 seconds before the end of the hunt and locking Kero away 11 seconds after the end of the hunt

- Top faction contributors:

- Dinos: , ,

- Cows: , ,

- Bees: , ,

- Dryads: , ,

- Boars: , ,

- All 1051 teams that played GalactiCardCaptors!

More stats

- 2,746 registered participants

- 3,591 hints answered (special thanks to Yannick and Wayne, who each answered around 1,500 hints)

- After the final battle, 28 teams chose to lock Kero back in the box, while 266 teams chose to have Kero join for some pie.

- 44% of teams thought that using the power of UWU to make more friends made sense.

- 59% of teams claimed to have read Chocolate Calf’s and Beeowulf’s card text upon starting the 4th stage of the tutorial.

- 74% of teams breezed through their first answerable, while 26% of teams thought it was tough.

Links

- Questions you asked us in the feedback form

- A themed YouTube playlist

Fan art (send us more!)

From @RedBirdRabbit (original tweet):

From @tetaes001 (original tweet):

Funny answers

Trigram Hell

- World's Delicacy Official Fan Club submitted UWU

- seals submitted SINCEBIRTHIHADAFAVOROFKETCHUPORMUSTARDINMYMEALINTHEOPPOSITEPOORLYLITHOLESSMALLSUBORDINATESHANDLETHEPROMEDIANTSSOLFEGEWELLNOTAYEARHASPASSEDWITHOUTMEMAKINGUSEOFIT

Petroglyph

- excavATE Minerals submitted GETSTICKBUGGED

Limericks

- 3 teams submitted PENGUINFIRE

- 7-2-15-25-26 submitted EGGBALL

- Pepsimen submitted ITURNEDMYSELFINTOALIMEMORTYIMLIMERICK

Make Your Own Star Battle

- The Managers submitted SINEWYSNAIL

Now I Know

- Isotopes Puzzles United submitted WAITTHECOMMONUSAVERSIONOFLETTERSONGGOESHIJKLMNOPTHATSVERYLOLSMHSMH

Gessner Mom

- small books and big data submitted HOUSTONSPOTTED and ILEARNEDTODRIVEONTHISHIGHWAY

- Quartzite Drillers (East) submitted COMEONDOWEREALLYHAVETOFIGUREOUTHOUSTONTEXASTRAFFICLAWS

- Deepspace Jeno1an Cave G1adiators submitted PLEASEJUSTONEMORELANEISWEARITLLFIXTHETRAFFICTHISTIME

Console-ation Prize

- Singles Ready to Stay Inside submitted MEWANTCOOKIE

- The Caroline Schism submitted STYOUGOTOBURKINAFASO

Beige Flags

- weeklies.enigmatics.org submitted THEREISABUGWITHFLAGS

#vent

- Quartzite Drillers (East) and Sufficiently Large N submitted AMONGUS

- possibly a heron submitted ISTHATANAMONGUSREFERENCE

- team_blet submitted ASDFJKLDKAHGASDJKL

- Welcome to the JuMBLE ⚛ submitted FJAFJKLDSKFJKFDJ

- :praytrick: submitted WHATPSYCHOPATHKEYSMASHESWITHNUMBERSINITAISHDGAHSDFGKASDFFGASDLFVBASLFB

Paint By Numbers

:praytrick: submitted:

- SPACED

- BRACED

- PLACED

- TRACED

- IAMSUBMITTINGTOTHEWRONGPUZZLE

Mastery Tree

Some teams got close to the answer…

- 8 teams submitted CAPTAINΠ

- 5 teams submitted OCAPTAINPICAPTAIN

- PuzzlePath Travelers submitted Π

- Insane Troll Logic submitted CAPTAINPIKACHU

- Cosmos Charting Challengers submitted CAPTAINOWO

- The Good, the Bad, and the Yoda submitted TAPIOCAPIE

Some teams tried answering the question directly…

- 3 teams submitted WORDPEACE

- Wizards of Aus submitted WORLDPEACE and THEPOWEROFFRIENDSHIP

- I'll keep you my twisty little passage (twisty little passage) / Don't tell anyone or you'll just be another backsolve submitted MANAJUICE

- Dora submitted BELIEVEINTHEHEARTOFTHECARDS

- if MATE has 1 MILLION fans i am one of them. if MATE has 1 THOUSAND FANS i am 1 of them. if MATE has 10 fans i am one. if MATE has 1 fan i am the fan. if MATE has no fans i am dead. submitted ONEHUNDREDYEARSINTHEINFINITEPAINCUBE

Gauss’s Sketches

if MATE has 1 MILLION fans i am one of them. if MATE has 1 THOUSAND FANS i am 1 of them. if MATE has 10 fans i am one. if MATE has 1 fan i am the fan. if MATE has no fans i am dead. submitted:

- HEREISALISTOFPHRASESWEREALLYLIKEFROMTHELIFEOFFREDPAGE

- WHYBLOWINGYOURNOSEANDWIPINGYOUREYESISNOTCOMMUTATIVE

- PIECHARTSCIRRHOSIS

- HOWTODEALWITHADUCKTHATNEVERTELLSTHETRUTH

Fun stories

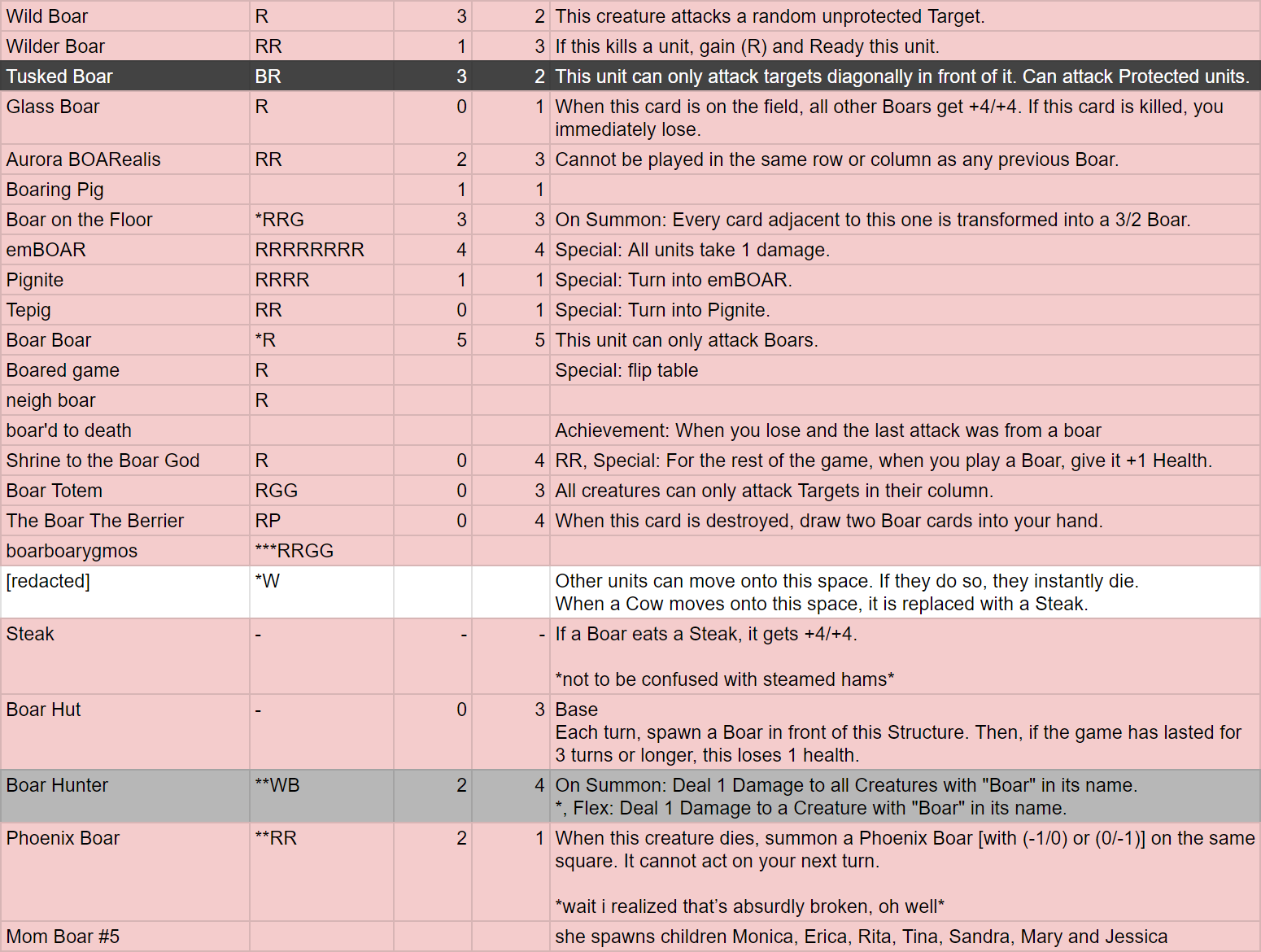

After the infamous writing retreat tournament where Boar (now ) was extremely strong and popular, our card ideas channel was full of new Boar cards:

And thus, the Boar faction was boarn.

We can’t forget Boarbie, who fell into relative obscurity...

Much of the inspiration of Cows come from these legendairy videos by ProZD.

One cut mechanic from GCC is the ability to customize the Bases you start with in each battle. We imagined being able to upgrade them and even specialize for particular factions (like producing 2 Boarries instead of 1 Pie). Here are some faction-specific Base concepts that never made it into the game:

- Clock Tower: alternates and production, also allows 1 use of conversion between and

- Beacon: +1 Power to adjacent Creatures.

- Yurt: Can Move. Creatures can be Summoned to Spaces adjacent to this Base as if they were Friendly. ( made it into The Swarm, without those abilities.)

- Library: Draw a card for 1 food instead of 2.

- Hatchery: Protect itself next turn instead of gaining Food.

There were many polish features that were almost cut from hunt because they caused our web team stress right before deadlines:

- Card animation in deckbuilding, including the holographic foil on Legendaries, inspired by Balatro

- Map art for Infinitely Many Hogs (and Logs)

- Animation for the Kero fight

We’re glad they made it in, we personally love them and we heard lots of positive feedback too!

WTFTadashi: I figured out Now I Know while driving my 4 year-old daughter home from pre-school. We had worked out that the words were shared between Baa Baa Black Sheep and Twinkle Twinkle. I was thinking about the puzzle in the car, and I kept singing the two songs and thinking about where the words overlapped. At one point, I was humming the tune, and my daughter started singing the A,B,C’s. That’s when it occurred to me that we had to also overlap the songs with the Alphabet Song. I suppose I should add her to the team roster now.

Gibbon Group managed to predict the final battle:

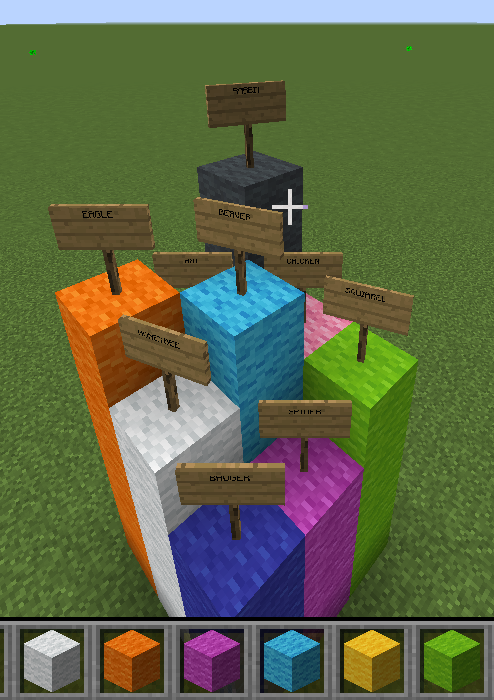

They also built Animal Shelter in Minecraft:

The Hunt Slayers appreciated the Slimes “a healthy amount”:

Eggplant Parms had a special strategy for Infinitely Many Hogs and Logs:

Credits

Chairs: Amon Ge, Yannick Yao

Art Leads: Chris Jones, DD Liu

Story: Kat Fang, DD Liu

Taskmaster: Jenna Himawan

Scribe: CJ Quines

Head Editors: Anderson Wang, Colin Lu

Editors: Charles Tam, Lewis Chen

Card Game Design: Charles Tam, Amon Ge

Onboarding Lead: Josh Alman

Email Lead: Alan Huang

Factchecking Lead: Jenna Himawan

Testsolving Lead: Kevin Li

Web Lead: Mark

Web: Alan Huang, Amon Ge, Andy Hauge, Brian Chen, Charles Tam, Chris Jones, CJ Quines, Colin Lu, DD Liu, Dominick Joo, Jenna Himawan, Jinna, Violet Xiao

Puzzle Writers: Amon Ge, Anderson Wang, Ben Yang, Brian Chen, CJ Quines, Charles Tam, Chris Jones, Colin Lu, Dai Yang, Jenna Himawan, Jinna, Josh Alman, Kat Fang, Kevin Li, Lewis Chen, Mark, Nathan Pinsker, Patrick Xia, Violet Xiao, Yannick Yao

Factcheckers: Anderson Wang, Andy Hauge, Charles Tam, Colin Lu, Dai Yang, Dominick Joo, Jenna Himawan, Jon Schneider, Max Murin, Sam Kim, Wayne Zhao, Yannick Yao

Postprodders: Amon Ge, Brian Chen, CJ Quines, Colin Lu, Jenna Himawan, Violet Xiao, Yannick Yao

Additional Testsolvers: Alwina, Andrew He, Bex Lin, Cameron Montag, Catherine Wu, Connor Tilley, Harrison Ho, Ian Osborn, Jacqui Fashimpaur, Katie Dunn, Leo Marchand, Leon Zhou, Lumia Neyo, Maddie Dawson, Rahul Sridhar, Steven Keyes, Tom Panenko, Vlad Firoiu